Slana Concentration Camp 1941

Remains of Slana Camp

Places on hold / Ana Opalić

The establishment of the ISC

On April 10, 1941, the Independent State of Croatia (ISC) was declared, comprising the greater part of today’s Croatia, as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina and eastern part of Syrmia that today lies within Serbian territory. Founded under the patronage of the Axis powers, that is Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, the ISC saw the Third Reich as its role-model when adopting both race laws and national legislation, which resulted in a series of statutes, rulings and ordinances that were issued over the weeks and months after its establishment.

These measures were primarily aimed against Serbs, Jews and Roma, making members of these ethnic groups “second-rate citizens”.

The policy of racial and national exclusiveness that was legally in effect by virtue of various legal provisions enabled the process of establishing the camp system in the ISC, which began to take shape in the second half of April 1941.

The first arrests and deportations ensued during the initial stage, when the first camps were also established: Danica, near Koprivnica, Kerestinec near Zagreb, the Jadovno camp on the Velebit mountain, near Gospić, the camps in the Slana bay and near the Metajna village on the island of Pag, as well as the camps in Kruščica near Travnik, in Đakovo…

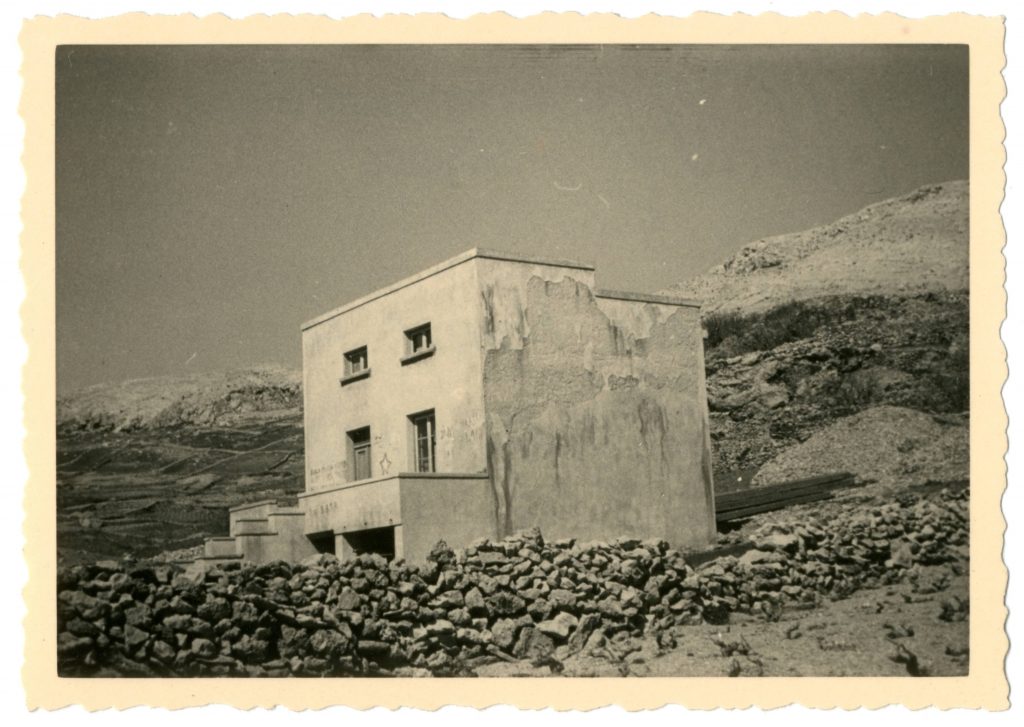

Image of the abandoned Slana camp, after the arrival of members of the Italian Army, September 1941 (all photographs) Source: Croatian History Museum

The Slana camp

In June 1941, the Jadovno-Pag camp system, with headquarters in Gospić, was established. This marked a new phase in the implementation of racial politics in the Independent State of Croatia. This camp system consisted of several camp units situated in Gospić itself, on the Velebit mountain and on the Pag island, with the main sites of mass executions being the Jadovno camp on Velebit and the Slana camp on Pag.

Mijo Babić, the commissioner of the Main Ustaša Headquarters, visited the sites on Pag in early June, after which it was decided that the women’s camp would be situated on the edge of the Metajna village, and the men’s camp on the barren rocky land of the Slana bay.

Along with Babić, Mijo Bzik, Milivoj Sažunić, Drago Hornung and Ivan Devčić “Pivac” also came to Pag to elaborate plans for the establishment of a camp on the island. They meet with the local canon Josip Felicinović, with whose help and on whose geographical map of Pag they determine the location of the future camp. Later, Felicinović’s unpublished manuscript about the camp, written in exile after the Second World War, will be used by historian Ivo Goldstein in the preparation of the book The Holocaust in Zagreb.

The Slana camp covered an area of around 5 hectares, around 5 km from the nearest settlement, Metajna. The conditions in the stony wasteland, directly exposed to the bora wind blowing from Velebit, with no potable water or vegetation, could not support any kind of normal life.

The first internees of the camp on Pag were Jews arrested in Zagreb on June 20, 1941. They were brought in Slana on June 24. That date can be considered the day this camp started working. The first group of detainees consisted of 30 Jews from Zagreb. At the time of their arrival, there was still nothing in Slana but bare stone.

After the Jews, Serbs and a small number of Croats, mostly communists, were brought. As of July 10, the number of Serbs is much higher. In the northern part of the camp there were mostly Serbs and to a lesser extent Croats, and in the southern part exclusively Jews.

The detainees were brought to Gospić in trucks and cattle wagons, and then had to walk to Karlobag. From there, they were transported to the camp by fishing boats, usually at night. The Ustashas used the boats of local people for this job, who were paid for the work done. Nine boats were used, and according to witnesses, some boat owners robbed detainees just as the Ustashas did. The detainees were pushed into the interior of the ship, beaten with boots and gunstocks, while some were killed and thrown into the sea.

Conditions in the northern part of the camp, where there were mostly Serbs, were worse than in the Jewish part. Upon arrival on Pag, many Serbs were taken directly to Furnaža, where they were killed without even coming to the camp. The northern part of the camp, separated by wire, was larger in area as well as in the number of detainees. These were mostly farmers arrested in coastal villages (for example in the village of Šibuljine), Lika and Bosnia. The Ustashas called them Chetniks and beat them immediately upon arrival at the camp. When they were lined up, unlike the Jews, they were not allowed to stand, but had to squat so that the guard could always kick them in the head. Detainees from the Jewish camp were not allowed to communicate with them, and Serbs were not allowed to approach other detainees.

The camp was surrounded by barbed wire, and watchtowers were built on the hills around the camp. Around the camp on the hills were Ustasha guards with rifles and machine guns.

Several barracks were built in the camp, made by the detainees themselves. These were low wooden buildings, or more precisely, wooden roofs or canopies erected on a low dry-stone wall. Only a small number of detainees could fit in them, while the rest slept in the open, on bare and sharp stones. In this place the days are extremely hot in the summer months, while the nights are very cold, especially when the bora is blowing.

The only brick building in the camp was the administrative building, which was also built by interns, and the remains of that building are still visible today. The detainees in the camp were subjected to the most difficult physical work, such as lime slaking and working in the quarry. They built a road from the camp to Metajna, the remains of which can still be seen today. In addition, they had to build watchtowers around the camp with their bare hands, dig a primitive latrine, build a kitchen for the Ustashas, and erect a barbed wire fence around the camp. They had no tools or aids. They had to carry stones, planks, logs, hay, stakes for fencing the camp and barbed wire, as well as other building materials, walking on sharp stones, some even without shoes. Every disobedience was punished by a firing squad.

The inmates were subjected to forced hard labour, building an access road to Metajna. Shifts lasted between 10 and 12 hours a day, in exhausting conditions, with constant abuse and beatings by Ustasha guards. Sanitary conditions were also disastrous, contributing to the development of various diseases.

Testimonies of detainees

Ante Zemljar brings the testimony of Otto Radan about working conditions and violence in the camp: „It was difficult to do any job under that terrible sun, hungry and tormented by an even more terrible thirst. Not to mention working with stone without any tools! It was horrible to separate and carry the stone for construction, either for the road, the watchtowers or elsewhere. The stones were carried by hand, without any other help. Silence, brickwork, endless line-up, shouts, fights, deaths around us and the constant death threat over each of us. We were wasting away, one by one, every day. For every little disobedience or clumsiness that the Ustasha guard would interpret as disobedience, a bullet would be shot. But they killed even without these reasons, just like that, out of the most ordinary pathological whim that any Ustasha could have whenever he wanted. He was not held accountable for that, on the contrary, he was probably praised and enjoyed a reputation among others.” (Zemljar, 1988: 56)

Food in the camp was very scarce, and the detainees were forced to eat grass and roots, but due to the rocky terrain and strong bora, there was almost no vegetation. Only in some places did a certain plant grow that proved to be poisonous. Surviving detainee Josip Balaž describes the food in the camp: „It was said that there were 500 of us in this place, and for all-day portions of food there were 20 kg of potatoes and 10 kg of flour. Unpeeled potatoes were put to boil, and then whisked raw flour was poured on them and that white watery mushy and disgusting food was an all-day meal that made most people get dysentery.” (Zemljar, 1988: 80). Many died of starvation and dysentery. They didn’t even get water, so they had to drink from the only spring in the area, but as it was on the beach in the same plane with the sea, the drinking water was mixed with seawater. It was therefore impossible to quench thirst.

The Ustashas took the detainees to swim in the sea. Testimony of Josip Balaž: „ From here they took us – they forced us on a daily basis to “swim” in a bay that was full and black of sea urchins, but when they forced us into the water, it turned red with human blood.” (Zemljar, 1988: 81)

Image of the abandoned Slana camp, after the arrival of members of the Italian Army, September 1941

The Metajna Camp

The camp for women and children on the island of Pag was situated in the Metajna village, north-west of the Slana bay. Women were held captive in two houses initially, later three, on the very edge of the village. The first inmates were four Jews, wives of men held in the Slana camp. They were most probably deported to Metajna on the same day that the men were to Slana, on June 24, 1941. The remaining women from this first transport were killed during deportation. They were followed by the women who had been captured earlier in Zagreb, as well as others who joined them in Gospić, who arrived sometime around July 15, 1941.

One of the few women who survived the Metajna camp, Nada Feuersien, has testified that there were around 275 women and children, Jews and Serbs, in the camp. She has described how women in the camp have sewed shirts for the Ustashe. The most distressing part of testimony relates to the rapes and murders of women in the camp.

After the Metajna camp, Nada Feuersien has testified that some of the women were deported to the Slana camp. Around 600 women and 78 children were held captive there. After the closure of the Slana camp, some of the surviving women were deported to the Krupčica camp near Travnik, after several days in transit.

Nada Feuereisen’s testimony:

“Upon our arrival on Pag, we disembarked on the shore below the Metajna village, and went there on foot. In Metajna, we were housed in two villas, 275 of us, women and children. Here we found women from the first and second transports. From the first, only four remained, the others, around 44 of them, having drowned during their journey. The four remained alive because they sewed shirts for the Ustashe. This was also the first time we met the boss of the Slana camp, lieutenant-colonel Devčić, nicknamed Pivac. The diet was minimal. We got beans for lunch, beans for dinner, food without spice and 120 grams of bread. The Ustashe sold us cheese, fruit and other foodstuffs at enormously inflated prices. After our departure, groups of Serb women started to arrive, among whom I knew mrs. Milinov, the elder, the wife of the judge Banjanin, their daughter and mother-in-law. There was a young clerk among the group of Serbs, her name was Sonja (I do not know her last name). One evening, the Ustashe took Sonja out, raped her, and after all the Ustashe took their turn, killed her and threw the body into the sea.”

In his unpublished manuscript, Joco Felicinović states that during his first visit to the abandoned camp in Slana at the end of August 1941. „in the main Ustasha barracks he found a piece of cardboard on the wall with records of the names and dates of women and girls raped in the camp, as well as names of those Ustashas who raped them.” (Goldstein: 289).

Witness Franjo Palčić testifies about the women’s camp in Metajna: „ All I know about the Slana and Metajna camps from my own observation is that in Dr. Triplat’s villa in Metajna large bloodstains were still visible on the mattresses, on two beds in the left room when looking from the seaside, on the first floor. I saw this with my own eyes in November 1943. According to the locals, whose names I do not remember, Jewish girls lived there and were slaughtered by the Ustashas in a villa and thrown into the sea at night, and one of them gave birth.” (Croatian State Archives, ZKRZ GUZ 2235/11-45)

Villas in Metajna, where women and children were held captive Source: Croatian History Museum

Mass killings

In addition to forced hard labour and poor sanitary conditions, the Ustashe also committed mass executions of inmates. These became more frequent after it was announced in August 1941 that the camp was to be closed.

Mass killings took place at a site near the camp, in a neighbouring bay known as Furnaža, above Paška Malina and Slana Bay. It was a deserted and rocky part of the island, such as Slana Bay, but here there was a thin layer of earth that allowed the burial of the dead in shallow graves. The detainees were brought from the camp to Furnaža by boats, and sometimes they arrived on foot. The Ustashas often threw the bodies of the detainees into the sea, with a stone tied around their necks. Detainees were mostly killed with side arms. In addition, there were individual killings of detainees in the camp itself.

The detainees were shot for the slightest disobedience, and the killings also took place without any specific reason because the Ustashas could treat the detainees however they wished. There was a lot of violence and murder in the camp. Public executions in which all detainees had to be present were frequent and were carried out especially in cases of attempted escape.

Most of the killings of detainees occurred just before the camp was disbanded. According to witnesses, hundreds of people were killed then. Witness Juraj Persen stated the following about these events before the National War Crimes Commission: „The biggest massacre was carried out on the eve of the Assumption. The day after that, i.e., on Assumption Day itself, about 60 Ustashas came to Pag, with the intention of participating in the procession and carrying the statue of Our Lady from the old town church to Pag, but noticing the displeasure of the local population, they gave up their original intention. Namely, they came to the church armed with still bloody knives, so that fact alone caused disgust to the peaceful inhabitants of Pag. At that time, there were rumours that the camp would be disbanded and that the Italians would take power on the island. The day before the disbandment of the camp, I went with Dr. Dodoja to the then Italian commander Bertoli, with the intention of interceding for the detainees, but Bertoli replied to Dr. Dodoja briefly, that it was too late „E gia tardi”. (Croatian State Archives, ZKRZ GUZ 2235/11-45)

According to the Rome Treaties of 18 May 1941 on the demarcation between the Kingdom of Italy and the Independent State of Croatia, the Gospić – Velebit – Pag camp system was in the Second Italian Occupation Zone. This zone belonged to the ISC, but with the constant presence of the Italian army. On August 16, the leader of the fascist party and the Prime Minister of Italy, Mussolini, sent a telegram to Pavelić asking for an urgent reoccupation of the area, due to the armed uprising that was spreading rapidly, and the inability of the ISC to bring it under control. This meant the immediate withdrawal of the Ustasha army from the area and the evacuation or liquidation of the camp. At that moment, Slana becomes a real death camp because a mass execution of surviving detainees takes place. In fact, the largest number of detainees were killed just before the evacuation. Between August 21 and 23, Slana was rapidly abandoned. The Ustashas leave the island, leaving behind a deserted camp and poorly concealed crimes. The corpses were covered only with a layer of earth and stone 10-15 cm thick. From Metajna to the lighthouse of St. Christopher there were 10 mass graves.

Excavation of mass graves within the Slana camp, September 1941 (all photographs) Source: Croatian History Museum

The closure and destruction of the Slana camp

The Rome Treaties between Fascist Italy and Ustasha ISC designated the area containing Velebit and the island of Pag as part of Zone B, which meant it was officially part of the ISC, but with the continuous presence of the Italian army. An additional treaty stipulated that for security reasons, the Italian army could retake full control over the area, including civilian administration.

In mid-August 1941, after information began circulating that Italy would demand the reoccupation of Zone B, the Ustashe began closing and destroying the camps on Pag and Velebit, which culminated in mass executions of inmates.

Vladimir Kustić, a fisherman from Pag, gave the following testimony about the night between August 14 and 15, 1941, which he had spent fishing in the Zaton area: „…when suddenly, long bursts of machine-gun fire pierced through the quiet night, mixed with the terrifying howls from Furnaža.”

Estimates of the number of detainees range from that given by the commander of the Italian crew on Pag, Captain Bertoli, who speaks of 4000 people, to boat owners who estimate the death toll at 15.000 and canon Felicinović from Pag who mentions 12.000 casualties in his manuscript, including 4000 women and children.

Only a few hundred detainees were taken from the camp after its liquidation.

During the reoccupation of the zone in which the camp system was located, around 400 last detainees were transferred to Karlobag, where some of them were killed.

In the chaos that accompanied the evacuation of Pag, a number of the inmates were killed on Velebit, their bodies discarded in karst pits.

Some of the detainees were transferred via Jastrebarsko to the Jasenovac camp (men) or Kruščica (women with children). Most men died in Jasenovac.

Two Italian army commissions visited the Slana camp area in September 1941, photographing its remains and the mass graves where men, women and children were found buried.

The Italian army was constantly on Pag. 6 km from the camp, there was an Italian crew consisting of one XXVII. GAF sector troop of 150 soldiers. They were very well informed about what was happening in Slana and Metajna, but they did nothing to prevent it. On September 3 and 22, two sanitary and disinfection commissions of the Italian Army visited Pag and submitted detailed reports to the Military Health Directorate of the 5th Italian Corps. The second commission was led by military doctor Santo Stazzi. The remains of the camp were also photographed at that time.

Sublieutenant Dr. Vittorio Finderle determines the existence of several mass graves and numerous smaller graves in and around the camp itself. He finds the corpses of men, women and children and concludes that many were killed and thrown into previously prepared pits, while many were thrown alive and buried after that. Given the fact that the bodies were very shallowly buried, Finderle concludes that there is a possibility of the infection spreading. Therefore, Lieutenant Dr. Santo Stazzi with 35 other Italian soldiers carried out the remediation of the cemetery. In doing so, the Italians took photographs of the camp and the exhumation itself, which are still in the holdings of the Croatian History Museum in Zagreb. Remediation lasted 10 days and began on September 11, 1941. Shallow graves were excavated, and corpses were burned on a pyre. Thus, 791 corpses were cremated, including 407 male bodies, 293 female bodies and 91 children’s bodies. The youngest child was 5 months old. It should be noted that they did not dig deeper graves, because they did not consider that there was a threat of infection from them. Only graves that were easy to locate and that were shallow were remediated. The terrain was never explored after that, and it is reasonable to believe that many those killed are still buried at that site. It should also be taken into account that according to eyewitnesses, the largest number of those killed were thrown into the sea.

After the disbandment of the camp, some of the inhabitants of Pag came to the site with the Italians. Nikola Bačić testified to the National Commission for War Crimes about what he saw: „ I was an eyewitness during the burning of the corpses of the unfortunate victims of the Ustasha terror on Slana, on September 9, 1941, when the Italian army with its medical detachments carried out the incineration. The evidence of inhuman torture was countless…” (Croatian State Archives, ZKRZ GUZ 2235/11-45). Duje Bilić testified similarly: „”I saw a woman whose belly was ripped open and there was a child in it, while she was holding another child in her arms. There were young girls, naked, whose breasts had been cut off. They all had traces of wounds from a knife and some blunt objects, probably stone. I searched to find empty shell casings, or maybe bullets, but since I didn’t find them anywhere, I conclude that the victims were slaughtered or stoned.” (Croatian State Archives, ZKRZ GUZ 2235/11-45)

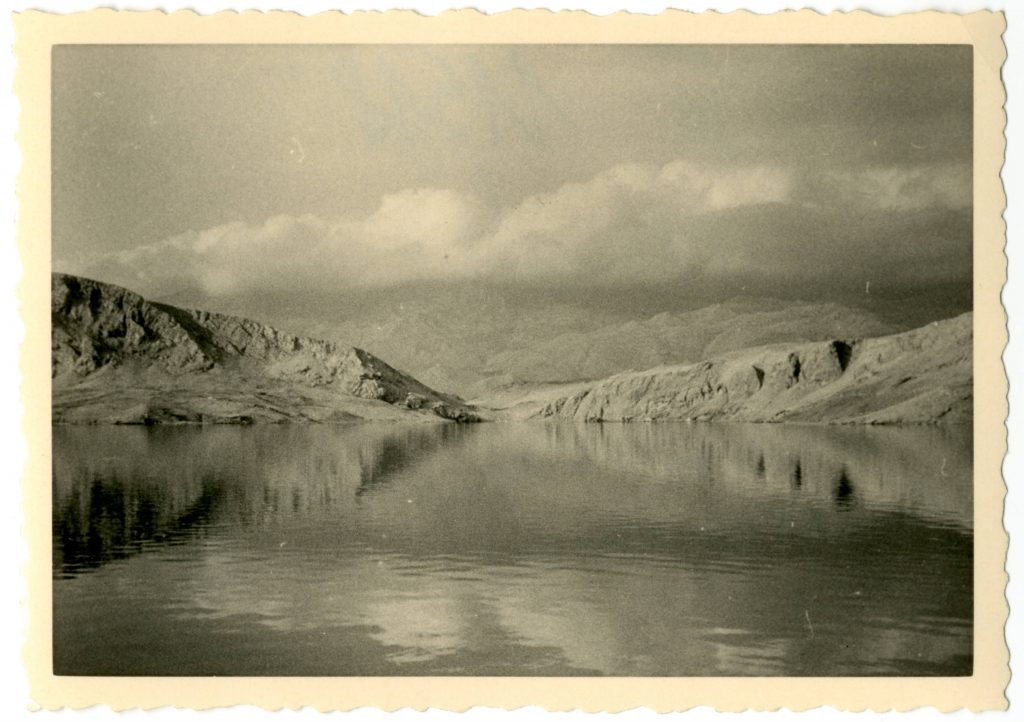

Photograph of the Slana bay from the sea. Source: Croatian History Museum

Memorialization

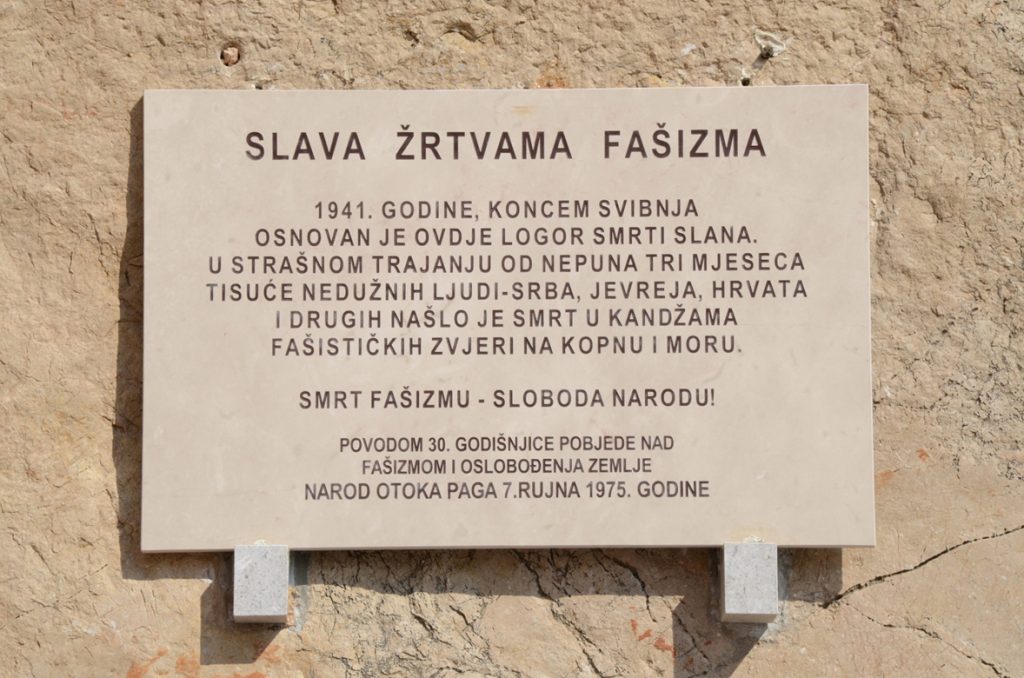

In November 1941, a group of League of Communist Youth of Yugoslavia members, including Ante Zemljar, placed a wreath of hawthorn thorns on the cross in the cemetery in Pag with two-meter black ribbons that read “Victims of – Slana”. This action can be considered the first erection of a memorial for the victims of the Slana camp. A memorial plaque has been erected several times in the bay itself. The Association of Fighters of the Island of Rab set it up for the first time in 1975. This plaque was destroyed in the early 1990s. The Serb National Council re-erected the memorial plaque in 2010 and 2013. Both times the plate was destroyed. The bust of Canon Josip Felicinović, who participated in the planning of the Slana camp and often visited it, is today located on the main square in the town of Pag.

Photo of the memorial plaque

Conclusion – remembering the inmates and victims of the Slana camp

In the central part of the island of Pag, there is a deep bay that opens to the north-east, facing the Velebit mountain. This landscape reminiscent of the lunar surface was where the Slana camp was situated.

The brutal conditions in the camp, as well as the equally brutal treatment of the inmates by the Ustashe, ensured that not many witnesses lived to tell the story of this place, making each preserved testimony precious. There were two sub-camps in the camp: one for the Serbs, and another for the Jews. According to testimonies by the few Jews who survived, the treatment of the Serbs was even more savage. As a result, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no cases of Serb inmates who survived the Slana camp and World War II and left testimonies about their experiences. For this reason, the testimonies of the surviving Jewish inmates are all that we have to inform us as to what took place in the Slana camp.

Keeping custody of the memory of the victims of the Slana camp was most often left to activists such as the writer Ante Zemljar, whose book, Charon and Destinies, is an indispensable read for anyone studying this topic. Today, the site where the camp was located is not marked by a monument or a memorial plaque.

Preserving memories of the victims of the Holocaust and of genocide is a cornerstone of civilisation because the victims must not be forgotten. Therefore, let us remember the victims of Slana.

Sources and literature

Books:

Goldstein, Ivo (2001) Holokaust u Zagrebu. Novi Liber, Židovska općina Zagreb: Zagreb

Zemljar, Ante (1988) Haron i sudbine. NIRO „Četvrti jul“: Beograd.

Archival Sources:

Hrvatski državni arhiv, fond ZKRZ GUZ 2235/11-45

Articles:

TEMAT: LOGOR SLANA http://www.zarez.hr/arhiva/387

Šimpraga, Saša (2014) Tri mjeseca Strave, Zarez: dvobroj 387 i 388 od 3. srpnja 2014.

http://www.zarez.hr/clanci/tri-mjeseca-strave

Konjikušić, Davor (2016) Slana to je njeno ime, Novosti,

https://www.portalnovosti.com/slana-to-je-njeno-ime

Exhibitions:

Exhibition “The Path of no Return – From the Slana Camp to the Jasenovac Camp” opened at Jasenovac Memorial

Exhibition “The Path of no Return – From the Slana Camp to the Jasenovac Camp”

Exhibition “The Path of no Return – From the Slana Camp to the Jasenovac Camp” opened in Beograd

http://www.jusp-jasenovac.hr/Default.aspx?sid=9301

Exhibition “Slana – the Radical Landscape ” opened in Zagreb

Author of the text

Ivo Pejaković

Editor

Vesna Teršelič

Proofreading

Đino Đivanović

Photography

Ana Opalić

Archival Photography

The Croatian History Museum

English translation

Hana Dvornik

Support

Stiftung EVZ

Acknowledgments for collaboration and support

The Croatian History Museum, Jasenovac Memorial and Documenta – Centre for Dealing with the Past staff