In Memory of Vladimir Turniški (1931 – 2026)

With sorrow we bid farewell from Vlado Turniški, a fighter, medical doctor and an important witness of the turbulent 20th and 21st centuries, grateful that he used every moment for the wellbeing of others, spreading the spirit of understanding, curiosity and respect. His wife Marija, daughters Vlatka and Maja, grandchildren Felix, Julius and Leopold and sons-in-law Michael and Predrag are most acquainted with his goodness of heart, diligence and integrity, but he did share a ray of that light with us as well.

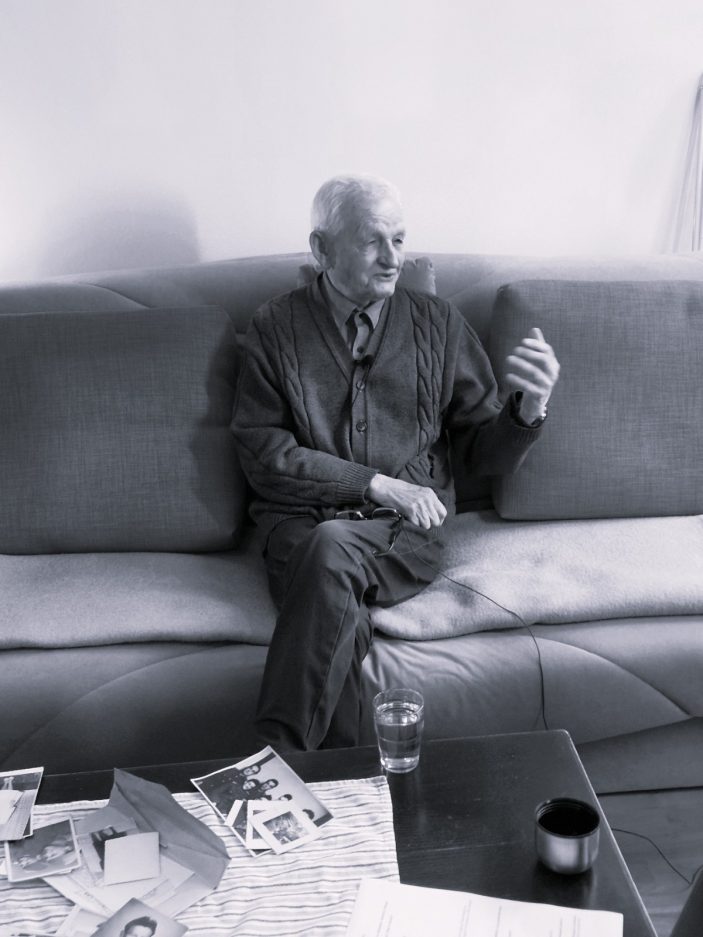

When we recorded his memories at Documenta, he led us through the places of his childhood, to the school near what is Dinamo’s stadium today and to the modest little house on Negovečka street. While he spoke about problems he encountered, he would also reveal important life lessons; very pedagogically, as if he was making a conscious effort to pass on his knowledge to everyone who might one day listen to his interviews. All of us were touched by his insights and calm wisdom without feeling angry for the circumstances that were difficult to change, like the very best of teachers.

He told us of the poverty of the 1930s. The “one meal they got in school” is what saved them. He added: “I don’t know whether we had a little milk and bread at home in the morning. There were 25 children in our class, many of them came from the Kolonija. As the youngest and second smallest, I always had to defend myself. We were from the south, poorer. My father bought me shoes that had metal rivets in the front and back that kept the sole protected. When one of my classmates flicked me, I kicked him in the shin with the shoe. After that, everyone started saying: “Don’t mess with him, he’ll fight back”. Turniški learned: “There’s nothing without a fight; it will be worse if you bow your head “.

While he was still in school, the war started. In Zagreb, during the winter of 1942/1943 hunger prevailed, and he went to get food, “…beans, potatoes, anything you could get” with his sister Dragica, who was two years older than him. They had an aunt in Crkvina near Bjelovar. The train stopped near Križevci, and Partisans searching for food entered. They fled when Ustaše approached. He rememberd seeing Partisans around Križevci.

On the route they took to school daily, he witnessed the Ustaše transporting Roma people by train, sending them on a journey of no return. His brother Leopold, who was born in 1924, perished in the Second World War. He was imprisoned and then deported in the summer of 1943. “Mum was crying, we ran after the train to give him something more”. They later learned that he had been taken to Austria for forced labour. That’s where they lost all track of him.

He did not like the Ustaše so he joined the Partisans the next summer 1944 with his friends, at the age of 13. They didn’t want to go before finishing the school year. They prepared for months, without telling their parents. “I told Branko I knew where the Partisans are, and August has come. Let’s go.” They boarded a train at Borongaj. “Around Dugo Selo the train hit a landmine, so we got off. We took another train and made it to Vrbovec without any checks at all… We were just boys, and all of us had a bag on us in which we put some bandages and got to the Partisans. They didn’t know what to do with us. They took them to another village where there were dozens of Partisan children of various ages.

Later he joined the 4th Vojvodina Brigade where he was accepted for courier duties. “We crossed the frozen river Drava near Bač… Wearing those same boots and uniform I came back home in 1945. My brigade moved down from Bjelovar toward Sesvete. The Partisans entered Zagreb from the south, not from the north. When the capitulation came, prisoners were already being driven downward, and we were moving upward. I saw people marching downward… We saw captured Ustaše and Domobrans (Home Guard) along the entire route, in Zagorje and in Slovenia… My unit went all the way to Bled. It was sometime in August 1945 when I came home… You can’t imagine my parents’ reaction, how happy they were. They were miserable when my father went to prison… and my brother had also been imprisoned in Petrinjska street, because of me. Naive, as a child, I did not take their suffering into consideration. I just thought there would be one burden less, one meal less. Who would think of such a burden…”

When he came back from the Partisans, he was regarded as a hero in his Negovečka neighborhood. “Suddenly everyone became very enthusiastic about the Partisans”. Soon after, the Partisan Gymnasium opened in Zagreb, at the corner of Gundulićeva and Boškovićeva streets, where Vladimir finished two more school years in just one year. He was the first in his family to buy books.

After that, he trained as a telegraph operator at a military school in Niš and began working in Požarevac at the age of sixteen. At seventeen, he was transferred to Priština, and later to Skopje. There, he held the rank of first-class sergeant and commanded 100 soldiers. “I looked at their faces, thinking how each one is different. Someone tells me that people were complaining that someone is stealing… And on one soldier’s face I saw it might be him… And indeed, in a few days, he was caught stealing some small items… That was when I realized how important it was to know people”. This curiosity later lead him to the study of medicine.

He welcomed the New Year of 1948 in Skopje, when there was already talk of tensions between Tito and Stalin. “I wanted to go home, not to prison”. He thought: “If you go bang your head against a wall, you pay the price.” And so, “from 1948 to 1952 I remained in the army in Niš against my will”. Already in Niš he realized: “To them, we were all Ustaše… I heard that from colleagues, but also from villagers… Then was when I decided to leave the army, that’s what the situation was in Serbia”. He requested discharge in 1950, and he was demobilized on December 1, 1952 and went back home to Zagreb”.

He started working in Vjesnik at the beginning of 1953 as a graphics apprentice in the typesetting department, soon moving on to work at a linotype machine. He still lived with Branko, Milan and Đurđa, “five of them in one room” In Negovečka street. He enrolled in evening school. He studied during the night completing his secondary education.

He met his future wife in 1954 at the entrance of the gymnasium. “I was leaning against the doorframe when a young girl came and said ‘I’d like go in’. We dated for eight years”.

He graduated in 1955 and later enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine. During the first half year, he asked his parents for support. “Only a small number of classmates knew I was supporting myself. Of the 600 people who started the first year, only 300 made it to the third.” He graduated from the Faculty of Medicine in Zagreb with the class of 1961/62.

When he began his medical internship, they lived modestly and struggled to make ends meet. “In 1956 and 1957 I was at the hospital on Zajčeva Street. The war in Pakistan had started, and they told me there was no place for specialization… Our daughter was born… We had nothing, the three of us in one little room… You couldn’t buy an apartment. I wondered if I was at fault, that I earned less than a typesetter, that I couldn’t provide a home for my family.”

Then they made a decision: “I had to leave a poor country… we could move to Germany or Sweden. We came to Sweden. Our older daughter Vlatka, born in 1963, was five years old.” There he learned a lot: “In Sweden, you learn to respect people. At home, they say, ‘He’s a Gypsy.’ In Sweden, that doesn’t exist. Everyone is the same.”

He didn’t visit relatives for years; it was too difficult, “that humiliation at the border.” They applied for Swedish citizenship, and in 1990 for citizenship of the Republic of Croatia. During the war, they collected aid and sent it to Croatia.

With a successful medical practice and shared work, they were able to afford a house. Vlatka went to study in Germany. Maja, born in 1972, began studying in the United States. The house became too large.

“Then came 1996. We took the car and went looking for a smaller house. And we found a little house on Murter. All the grandchildren were born in Germany. From that misery, everything turned into love. I always tell the children: don’t carry Hitler’s burden—you are responsible only for your own actions.”

With a smile, he shared his life philosophy: “I achieved everything—that means only work, nothing more… When you help a young person set realistic goals, they will accomplish whatever they want. When a doctor takes works seriously, he values every moment; there are no shortcuts in life… A patient who suffers does not ask whether you have time.”

In his later years, he took pride in the garden he tended beneath the window of his modest apartment in Maksimir, emphasizing: “You must have an ethical standard…” And to all of us, he advised: “Just close ranks and get rid of the thieves.”

Grateful for his life and all the lessons he gave, I can only add: may the earth rest lightly upon you.

Vesna Teršelič